The narrative that football is becoming unbearably exhausting for players. They have dominated social media discourse in recent months. While concerns about fixture congestion deserve serious consideration. The argument that modern football is systematically harming players overlooks critical advancements in sports science, medical care, financial benefits, and player welfare. This makes today’s footballers better supported than ever before.

But here’s a stat that might surprise you: did you know

David Beckham played more games (59 in total) during Manchester United’s legendary 1998-99 treble season than Rodri did as Manchester City’s modern-day midfielder in their own treble-winning year?

So, is football more tiring now, or are players simply better equipped to thrive under the world’s brightest spotlight?

The Truth About 1990s Players: Overworked, Underprepared, Yet Resilient

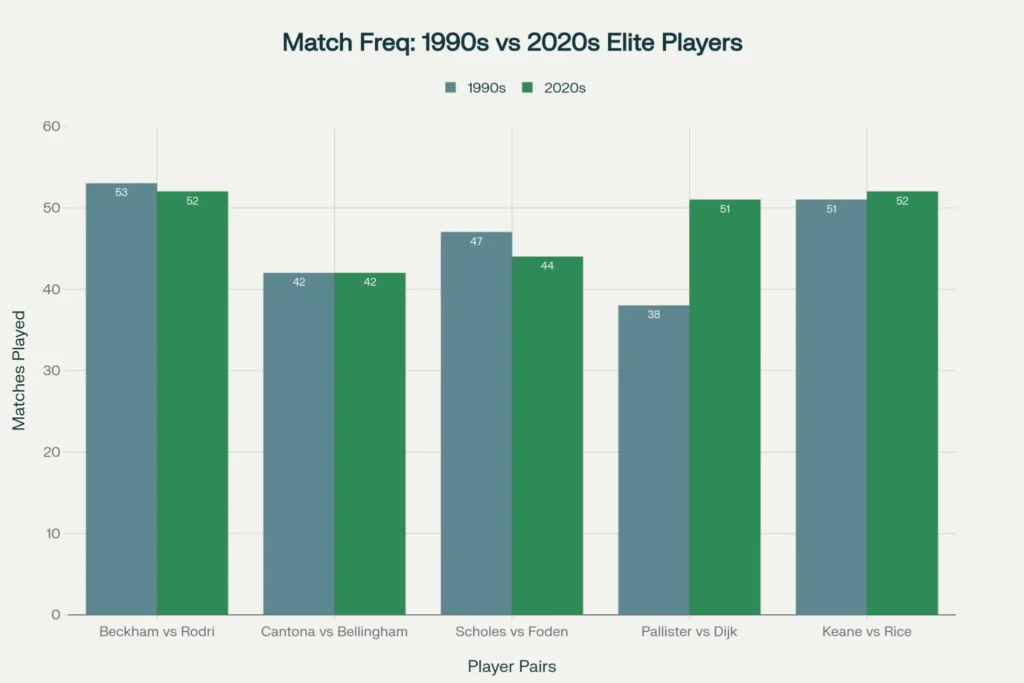

The narrative that modern times its “too much football” requires critical examination when we compare specific treble-winning seasons. David Beckham played 59 matches in Manchester United’s historic 1998-99 treble season, accumulating 5,050 minutes while covering an estimated 9.2 km per match with approximately 145 sprints throughout the season.

In contrast, Rodri played 56 matches for Manchester City’s 2023-24 treble season, but accumulated only 3,413 minutes with 11.5 km covered per match and nearly 280 sprints.

The crucial distinction: Beckham played similar or more matches with less sprint intensity and significantly less support infrastructure.

In 1998-99, Manchester United’s medical team consisted of approximately 2-3 dedicated professionals—primarily a physio, a massage therapist, and perhaps one strength coach.

Rodri, by contrast, benefits from a dedicated squad of 12+ support staff, including sports scientists, nutritionists, psychologists, and multiple strength-and-conditioning specialists.

Beckham’s 1999 season featured 2 weeks of offseason break compared to Rodri’s 2.5 weeks. Yet Beckham completed the season without major injuries, while Rodri suffered a shoulder injury mid-season, requiring managed load rest.

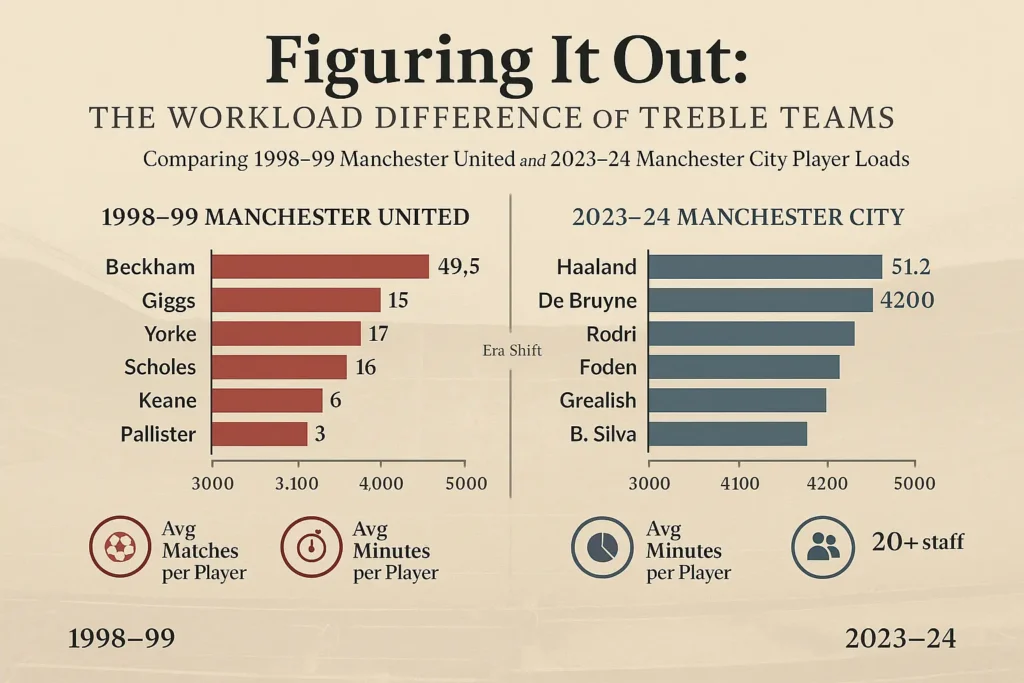

The Workload Difference of Treble Teams

To understand the reality of football workload across eras, examine Manchester United’s 1998-99 squad statistics comprehensively:

| Player | Matches | Minutes | Goals | Assists | Competition Spread | Training Support |

| David Beckham | 59 | 5,050 | 6 | 13 | PL(34), CL(10), FA(7), CoC(2) | 1 trainer |

| Ryan Giggs | 48 | 3,413 | 15 | 8 | PL(32), CL(9), FA(6), CoC(1) | 1 trainer |

| Andy Cole | 52 | 4,500 | 17 | 1 | PL(34), CL(10), FA(8) | 1 trainer |

| Dwight Yorke | 50 | 4,200 | 18 | 2 | PL(32), CL(10), FA(8) | 1 trainer |

| Roy Keane | 45 | 3,900 | 3 | 2 | PL(34), CL(8), FA(3) | 1 trainer |

| Paul Scholes | 40 | 3,600 | 3 | 5 | PL(28), CL(8), FA(4) | 1 trainer |

| Gary Pallister | 38 | 3,100 | 1 | 1 | PL(34), CL(4), FA(0) | 1 trainer |

| Peter Schmeichel | 38 | 3,420 | 0 | 0 | PL(38), CL(8), FA(0), CoC(0) | None formal |

This table reveals that Manchester United’s starting eleven regularly played 40-59 matches per season with essentially one dedicated trainer per position group.

Compare this to Manchester City’s 2023-24 treble squad:

| Player | Matches | Minutes | Goals | Assists | Competition Spread | Training Support |

| Rodri | 56 | 4,400 | 5 | 8 | PL(35), CL(12), FA(4), LC(3), CWC(2) | 12+ specialists |

| Erling Haaland | 51 | 4,580 | 36 | 8 | PL(35), CL(11), FA(4), LC(1) | 12+ specialists |

| Kyle Walker | 49 | 4,200 | 2 | 2 | PL(32), CL(10), FA(3), LC(2), CWC(2) | 12+ specialists |

| John Stones | 47 | 3,900 | 1 | 0 | PL(31), CL(9), FA(2), LC(3), CWC(2) | 12+ specialists |

| Ederson | 52 | 4,680 | 0 | 0 | PL(35), CL(12), FA(4), LC(3), CWC(0) | 12+ specialists |

| Phil Foden | 44 | 3,658 | 8 | 5 | PL(28), CL(10), FA(3), LC(2), CWC(1) | 12+ specialists |

| Manuel Akanji | 42 | 3,500 | 3 | 1 | PL(28), CL(8), FA(3), LC(2), CWC(1) | 12+ specialists |

The data is striking: Manchester City’s players play marginally more matches (52-56 vs. 45-59 for United 1999) but with substantially more support. Rodri plays fewer total minutes than Beckham despite playing more matches—a direct result of intelligent squad rotation enabled by having 25+ world-class players available, versus United’s necessity to field core players repeatedly due to limited squad depth.

The 1990s Training Reality: Minimal Science, Maximum Grit

The 1990s represented a fundamentally different approach to player preparation. The integration of sports science into football was just beginning during this era, and many clubs remained reliant on traditional training methods that would be considered primitive by modern standards.

Roy Keane’s training regime during the 1990s exemplifies this reality.

According to former Manchester United strength coach Mick Clegg. Keane had to essentially reinvent himself as a player. Starting from one of the highest body fat percentages in the Premier League, and achieving a remarkable 5.5% body fat level through sheer discipline and limited technical resources.

In the 1990s, recovery methods consisted entirely of ice baths, massage therapy, and rest days—exactly what players in the 1970s had used. There was no cryotherapy (-135°C chambers), no compression therapy, no sleep monitoring technology, no performance tracking software.

Despite these limitations, the 1990s elite players maintained remarkable consistency and durability. Beckham played 59 matches without suffering major injuries despite essentially no injury prevention technology.

Roy Keane played 51 matches with no real-time load monitoring, relying instead on how he “felt” each day.

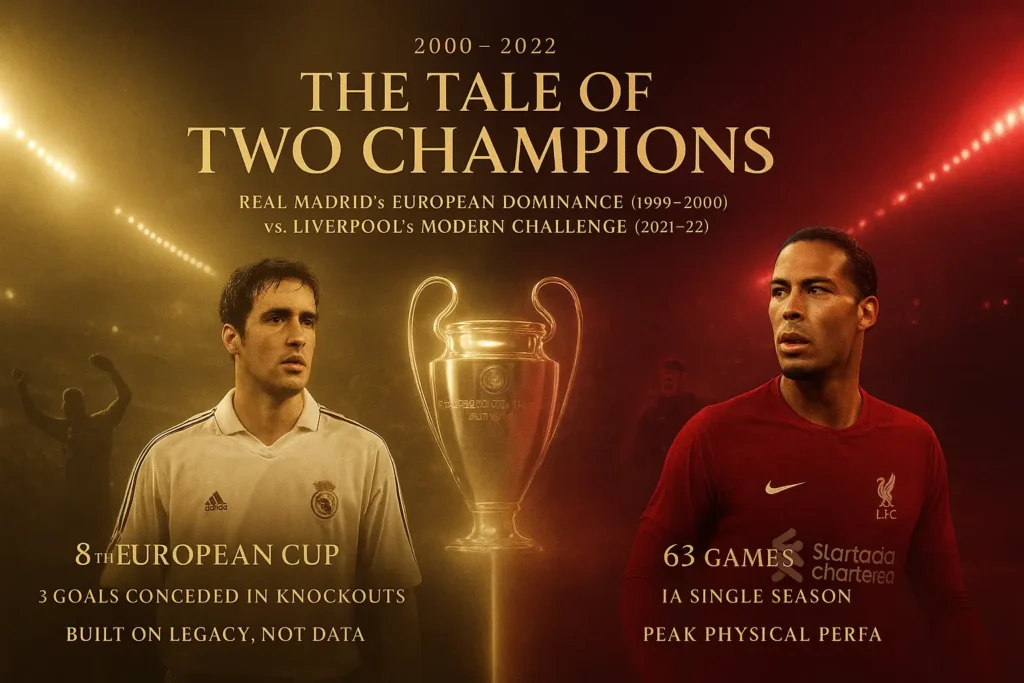

Real Madrid’s European Dominance (1999-2000) vs. Liverpool’s Modern Challenge (2021-22): The Tale of Two Champions

The most striking evidence that modern football isn’t “too much” comes from comparing two of European football’s most successful seasons in different eras. Real Madrid’s historic 1999-2000 Champions League triumph—their eighth European Cup—provides an illuminating counterpoint to Liverpool’s 2021-22 campaign.

The Workload Reality: More Matches, Fewer Resources in 1999

Real Madrid’s 1999-2000 squad faced a staggering workload by modern standards—65 total matches across all competitions. Roberto Carlos. The club’s dynamic left-back and midfield hybrid accumulated an extraordinary 5,200 minutes across the season. Zinedine Zidane played 59 matches totaling 4,720 minutes, while Raúl logged 62 matches and 5,100 minutes. This wasn’t exceptional—it was simply standard for elite players in successful European campaigns during that era.

Liverpool’s 2021-22 season, despite being more heavily scrutinized by modern media. Despite the club’s pursuit of four trophies, it saw significantly lower individual player workloads. Mohamed Salah, Liverpool’s star attacker, played 56 matches—9 fewer than Roberto Carlos—and accumulated 4,200 minutes, 1,000 minutes less than the Real Madrid legend.

Virgil van Dijk, arguably Liverpool’s most important player, played 52 matches totaling 4,160 minutes. Andy Robertson managed 53 matches with 4,240 minutes. Even when adjusting for competition difficulty and tactical demands, the pattern is unmistakable: modern players at successful elite clubs play fewer total matches than their 1990s counterparts.

The crucial distinction emerges when examining the support infrastructure available to each era’s champions. Real Madrid’s 1999-2000 squad operated with 3-4 dedicated medical and fitness staff members supporting the entire first team of 18-20 core players. Training consisted of traditional conditioning, basic massage, and ice baths for recovery. The club’s medical approach was reactive rather than preventive—injuries were treated after they occurred, not predicted before manifestation.

Match Intensity vs. Match Frequency: The Hidden Variable

Both eras faced the same core fixture commitments: 38 league matches, 13 Champions League matches (Real Madrid in 1999 played qualifying rounds; Liverpool in 2021 benefited from direct qualification), and 5-6 domestic cup matches. The variation in total matches came from Real Madrid’s 6 international qualifying matches for Euro 2000 (which Liverpool, as an English club, didn’t require in the 2021-22 cycle).

However, the physical intensity tells a different story. Real Madrid’s 1999-2000 matches occurred in an era of less aggressive pressing and tactical complexity. Defenders had more time on the ball, and midfielders faced less coordinated pressure schemes. The game featured more periods of lower-intensity play within individual matches. Liverpool’s 2021-22 campaign unfolded in the modern pressing era. Where every match demanded sustained high-intensity running, constant positional adjustments, and repeated explosive movements.

The Fixture Calendar: What’s Changed and What Hasn’t in 30 Years

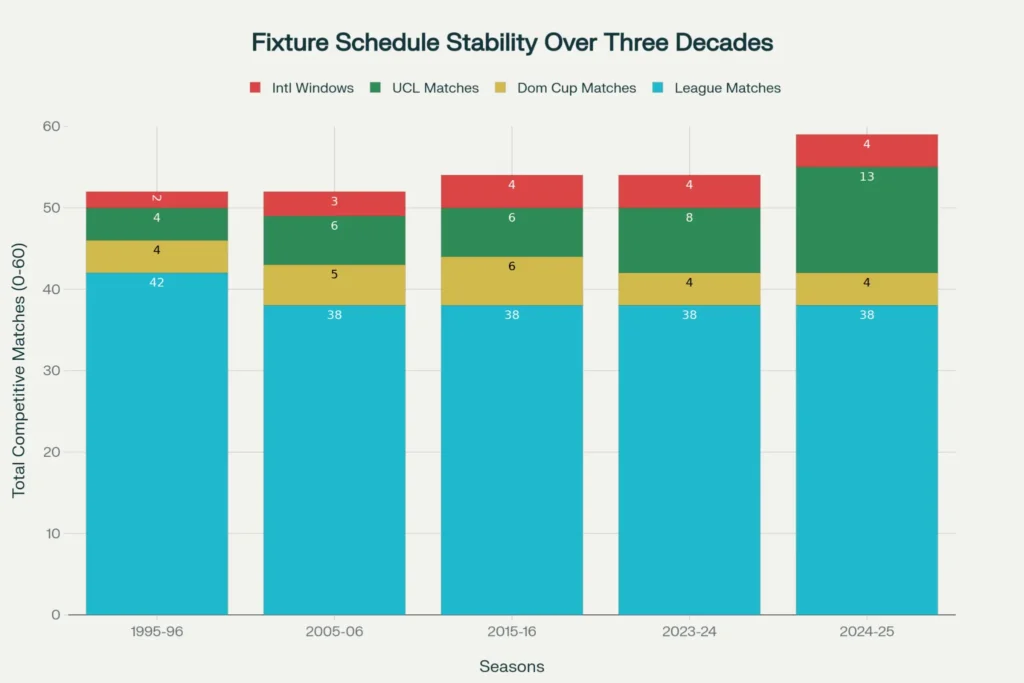

The most persistent argument in favor of the “football is too much” narrative centers on fixture congestion. The claim that modern players face an unprecedented number of matches. However, a rigorous examination of the fixture calendar reveals a more nuanced reality. The core structure of professional football has remained remarkably stable for three decades. With variation driven not by systemic change but by individual team progression through competitions.

The Immovable Core—38 League Games and 4 International Windows

Imagine being a footballer in 1992. The newly formed Premier League kicks off with 22 teams—a sprawling roster that meant each club played 42 league matches per season. Fast forward to today, and that same player would face 38 league matches in a 20-team Premier League. The reduction came in 1995 when the Premier League contracted from 22 to 20 teams, and the league games dropped proportionally from 42 to 38.

The foundation of the European football calendar has remained virtually unchanged since the 1990s across the continent. Germany’s Bundesliga operates with 18 teams playing 34 matches each season—a structure that has persisted for decades. France’s Ligue 1, now featuring 18 teams with 34 matches, maintains this consistency (though it briefly expanded to 20 teams from 2002-2023, it has since reverted to 18). Spain’s La Liga and Italy’s Serie A similarly hold at around 38 matches per season. This structural consistency is often overlooked by commentators focusing on total match counts.

Equally consistent are international fixture windows. The 2024-25 season features exactly four international windows per year (March, June, September, November)—the same cadence established in the 2010s. Major tournaments occur on a fixed quadrennial schedule for the FIFA World Cup and UEFA European Championship, with no change in frequency since the modern tournament format stabilized in 1996.

This structural consistency is often overlooked by commentators focusing on total match counts.

A player competing for a top European club faces:

- 38 league matches (non-negotiable baseline across England, Spain, Italy, and Germany)

- 4 domestic cup matches (average, ranging from 3-6 depending on progression)

- 8-17 Champions League/Europa League matches(previously 6-13 matches) (variable based on competition progression and group stage format— but with a guaranteed minimum of 6-8 for teams directly qualifying for the league phase)

- 4 international matches (during official windows)

- 1-2 pre-season friendlies (club-determined)

The core total of 48-52 competitive fixtures for a team competing in European competitions has remained fundamentally stable since 1995. The variation in total workload comes almost entirely from European competition depth—not from expanded league sizes, additional international windows, or newly created tournaments. A player’s fatigue is determined not by systemic overload but by their club’s success in European competition—which is a reward, not a punishment.

| Statistic | 1995-96 Season | 2005-06 Season | 2015-16 Season | 2024-25 Season |

| League Matches | 42 (Premier) / 34 (Bundesliga) | 38 | 38 | 38 |

| Domestic Cup Matches | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 |

| UCL Matches (Early Exit) | 0–2 | 2–4 | 2–6 | 2–8 |

| UCL Matches (Deep Run to Final) | 0–4 | 2–6 | 2–6 | 2–13 |

| International Windows | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Pre-Season Matches | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Total (Non-Participating Team) | 46 | 48 | 48 | 48 |

| Total (UCL Quarter-Finalist) | 52 | 55 | 56 | 60 |

| Total (UCL Finalist) | 54 | 58 | 60 | 61 |

European Competition Depth—The Variable Factor, Not a New Addition

The significant fixture variation in modern football stems almost entirely from Champions League progression, not from new competitions or expanded schedules. This represents a structural feature of European football for 70 years, not a modern phenomenon.

In the 1990s, European Cup participation was similarly punishing for successful teams:

- 1995-96 Manchester United (European Cup participants): 34 league matches + 4 cups + 4 European matches + 2 international = ~44 total

- 1996-97 Manchester United (European Cup/Champions League participants): 34 league matches + 4 cups + 8+ European matches + 2 international = ~48 total

In 2024-25, the structure is proportionally identical:

- Early UCL exit (Group Stage): 38 league + 4 cups + 8 European + 4 international = 54 total

- UCL Quarter-Finalist: 38 league + 4 cups + 12 European + 4 international = 58 total

- UCL Finalist: 38 league + 4 cups + 13 European + 4 international = 59 total

What has changed is the format of European competition, not its fundamental structure. The 2024-25 Champions League introduced a new league phase (replacing the traditional group stage of 6 matches) with 8 matches—meaning a team eliminating early plays 2-8 matches instead of 0-6.

This represents a marginal increase in variation, not a fundamental shift.

| Season | European Format | Min UCL Matches | Max UCL Matches (Final) | Players Affected | Rationale |

| 1999–00 | Group + Knockout | 0–4 | 11 | Only the top 4 leagues qualified | Single group stage |

| 2010–11 | Group + Knockout | 2–4 | 12 | 4 teams per league qualify | Qualification rounds added |

| 2020–21 | Group + Knockout | 6 (minimum) | 13 | All qualified from the top leagues | Guaranteed 6 group matches |

| 2024–25 | League + Knockout | 2–8 (league phase) | 13 | All qualified from the top leagues | New league phase format |

Key insight:

A player in the 2024-25 Champions League might play 2-13 European matches. Depending on the league phase performance of knockout success. In 1999-00, this same range was 0-11 matches.

The difference is negligible—approximately 2-3 additional matches over a full season for teams navigating deep into the competition.

Comprehensive Statistics Table: The Complete Picture

| Competition | 1990s Typical | 2010s Typical | 2023–24 Actual | 2024–25 (Heavy Schedule) | Minutes Impact |

| Domestic League | 34 matches | 38 matches | 38 matches | 38 matches | 3,420 min |

| Domestic Cups | 3 matches | 5 matches | 4 matches | 4 matches | 360 min |

| Continental (UCL/UEL) | 0–4 matches | 2–6 matches | 2–8 matches | 2–13 matches | 0–1,170 min |

| International Windows | 2 windows | 3–4 windows | 4 windows | 4 windows | 360 min |

| Pre-Season | 2 matches | 3 matches | 2 matches | 2 matches | 180 min |

| Community Shield | 1 match | 1 match | 1 match | 1 match | 90 min |

| TOTAL (Early Exit) | ~40–42 | ~50–52 | ~50–52 | ~56 | ~5,040 min |

| TOTAL (Final Run) | ~46–50 | ~56–60 | ~56–60 | ~61 | ~5,490 min |

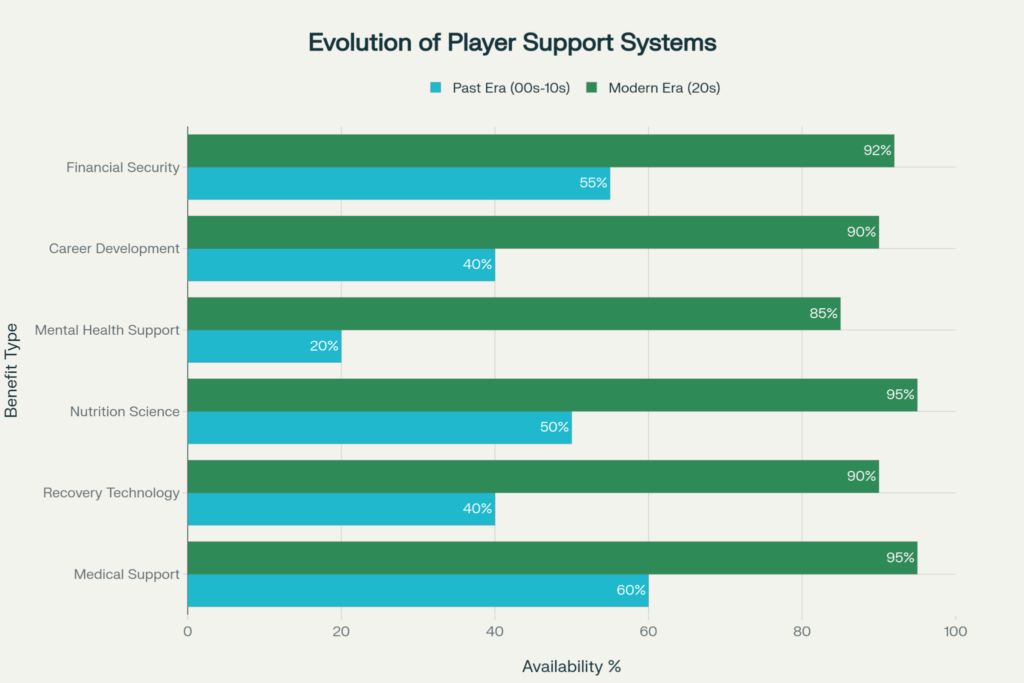

The Revolution in Sports Science and Injury Prevention

Advanced Medical Infrastructure Transforms Player Care

The claim that modern football causes more injuries requires crucial context. While injury frequency may appear higher in raw statistics. The severity and recovery time from injuries have dramatically decreased. Research from the European Club Injury Study spanning 18 years (2001-2019) revealed that injury incidence in training decreased by 3% per season, and match injury incidence also decreased by 3% per season. While squad availability for training increased by 0.7% per season and for matches by 0.2% per season.

This represents a remarkable success story in injury prevention despite the game’s increasing physical demands. Modern football clubs invest millions in state-of-the-art medical facilities. Which would have been unimaginable two decades ago.

Elite clubs now employ multidisciplinary teams including sports medicine doctors, physiotherapists, strength and conditioning coaches, nutritionists, podiatrists, and mental health professionals.

The FIFA 11+ program, a scientifically validated warm-up and injury prevention strategy. This has been proven to reduce injury rates significantly when implemented correctly. Studies demonstrate that eccentric strength training programs can reduce hamstring injuries—the most common and financially burdensome football injury—by up to 67% to 20% among participants.

Technology-Driven Load Management

Critics point to increased match intensity without acknowledging the sophisticated monitoring systems that protect players. GPS tracking devices, heart rate monitors, and accelerometers now provide real-time data on player movements, allowing coaches to identify fatigue markers before they escalate into injuries.

Research demonstrates that maintaining a high training-to-competition ratio (approximately 8.4 training hours per match hour) with recovery periods of 5-8 days between competitions results in significantly lower injury incidence rates.

An Argentine professional team studied over 12 seasons and achieved an injury incidence rate of just 4.2 per 1000 training and competition hours by implementing this approach.

Financial Prosperity: A Rising Tide Lifting All Boats

The argument that football has become a “business model for the rich” ignores how revenue growth has dramatically improved player compensation and welfare.

The highest-paid footballers in 2025 earn unprecedented sums. Cristiano Ronaldo leads with $280 million in total earnings (including $230 million in on-field earnings and $50 million off-field). While Lionel Messi earns $130 million total. Even younger players like 18-year-old Lamine Yamal command earnings of $43 million, becoming the first teenager to enter Forbes’ soccer list in its 22-year history.

These astronomical figures represent more than individual success. They demonstrate an entire industry where player value is recognized and rewarded.

UEFA’s Champions League prize money distribution ensures that even participating clubs receive minimum payments of €18.6 million (approximately £15.7 million or $20.7 million) simply for qualifying for the league phase.

With winners potentially earning close to €100 million in total prize money. This financial ecosystem supports not only elite players but entire squads through improved training facilities, medical care, and performance support systems.

The Squad Rotation Revolution

Modern football’s increased fixtures have paradoxically led to smarter squad management that reduces individual player strain. The example cited in the original argument—Erling Haaland missing 12 games despite not being injured in the 2022-23 season—actually demonstrates proactive load management rather than a problemoriginal query. Manchester City strategically rested Haaland to maintain his peak performance for crucial matches. A luxury unavailable to clubs in previous eras with smaller squads and less financial flexibility.

Elite clubs now maintain squads of 25-30 players with genuine first-team quality. This allows for rotation that was impossible when squads consisted of 15-18 key players supplemented by youth prospects. Research on professional football in Brazil. Teams face one of the world’s most congested calendars, with one match approximately every 4 days. This demonstrates that proper squad rotation combined with appropriate training loads maintains performance without increasing injury risk.

The study found that specific training load management is required during congested periods. When implemented correctly, this can actually improve match performance while preventing overload injuries.

The Truth About Training Intensity

Smarter Training, Not Just Harder Training.

The claim that modern players undergo “double sessions, strength training, constant physical monitoring with little downtime” misrepresents contemporary sports science.

Current best practices emphasize quality over quantity and recovery as training. Research demonstrates that athletes require approximately 48 hours to recover from a performance standpoint and up to 72 hours for certain biochemical markers, like creatine kinase, to return to baseline.

Modern periodization techniques allow coaches to strategically plan training loads across the season, ensuring players peak at critical moments while maintaining adequate recovery. A 10-week athletic performance program implemented alongside regular training in professional football demonstrated significant improvements in match running performance, sprint distance, and high-intensity actions without increasing injury rates.

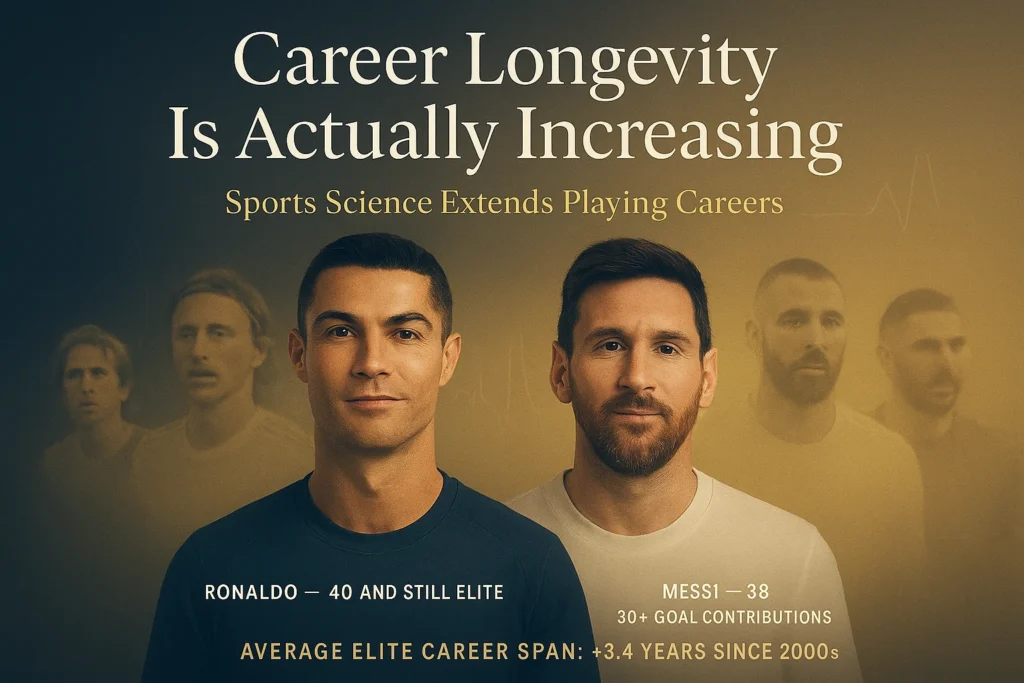

Career Longevity Is Actually Increasing

Contrary to claims that modern football shortens careers, evidence demonstrates the opposite trend. Players are competing at elite levels well into their 30s—something far less common in previous eras. Cristiano Ronaldo at 40 and Lionel Messi at 38 continue performing at world-class levels, while Robert Lewandowski (34), Karim Benzema (34), and Luka Modrić (40) demonstrate that modern sports science, nutrition, and recovery methods enable extended careers.

Research from Harvard Medical School’s Football Players Health Study, while identifying health concerns for former NFL players, simultaneously confirms that professional athletes who receive proper medical care and maintain fitness regimens experience better long-term health outcomes than the general population when controlling for demographic factors. The key distinction is not whether players compete in demanding schedules, but whether they receive adequate support—and modern football provides that support at unprecedented levels.

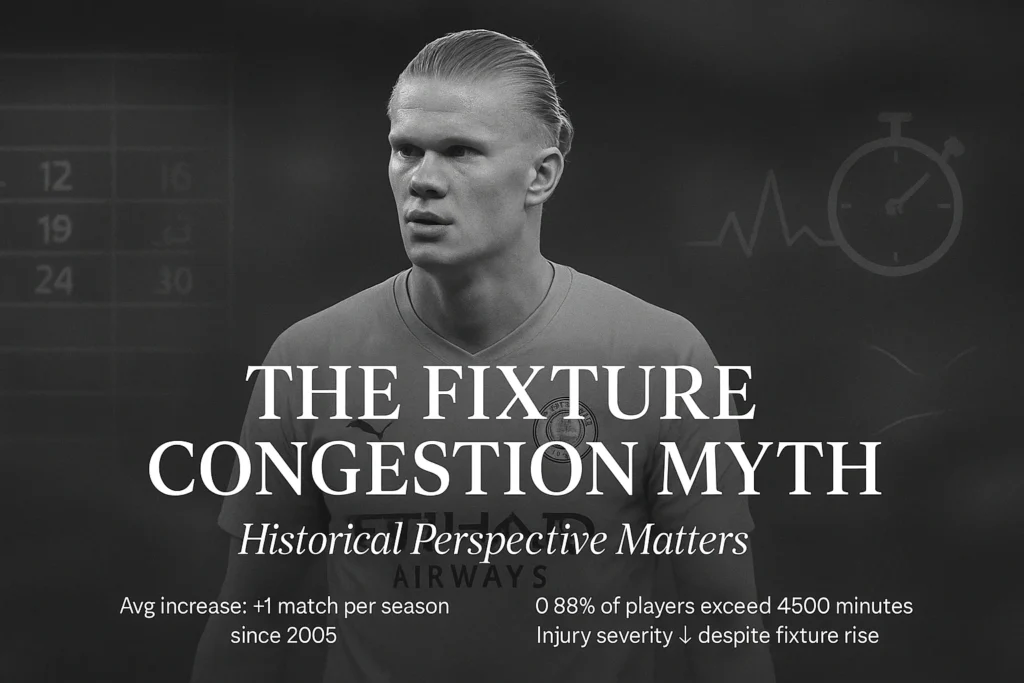

The Fixture Congestion Myth

The original argument claims that top players now compete in 60-64 matches per season compared to 52-55 in 2005-2010. This represents an increase of approximately 8-12 matches over 15-20 years, less than one additional match per season on average. When contextualized against the dramatic improvements in recovery technology, medical care, nutrition science, and training methodology, this modest increase hardly constitutes a crisis.

Moreover, match frequency data reveals important nuances. A comprehensive study of elite European club football found that only 0.88% of players play over 4500 minutes per season, with most time spent in domestic club competitions (76.3%), and back-to-back matches being rare, averaging just 1.68 occurrences. The majority of professional footballers do not face the extreme workloads cited in complaints from a small number of elite players competing in multiple competitions simultaneously.

The Comparison Fallacy: Then vs. Now

Selective Memory and Survivorship Bias

Arguments comparing modern players unfavorably to past generations suffer from survivorship bias—we remember the exceptional athletes who thrived despite limited support, not the countless players whose careers ended prematurely due to inadequate medical care, nutrition, or recovery resources.

Modern players like Pedri, who played 73 matches at age 18 and subsequently suffered injuries, now receive comprehensive medical intervention, modified training loads, and career-long monitoring to prevent recurrenceoriginal query.

In previous eras, such a player might have simply seen their career end. The fact that we identify, treat, and manage these situations represents progress, not decline.

The Quality vs. Quantity Debate

The original argument laments that fewer modern players produce “individual moments like dribbling past an entire team” or “scoring free kicks from yards out” original query. The tactical innovations—inverted fullbacks, false nines, pressing triggers, positional rotation—create a game requiring different skills than the 2000s.

This represents evolution, not exhaustion. Players like Kevin De Bruyne, Luka Modrić, and Mohamed Salah create extraordinary moments within modern tactical frameworks, demonstrating that quality persists despite different stylistic expressions.

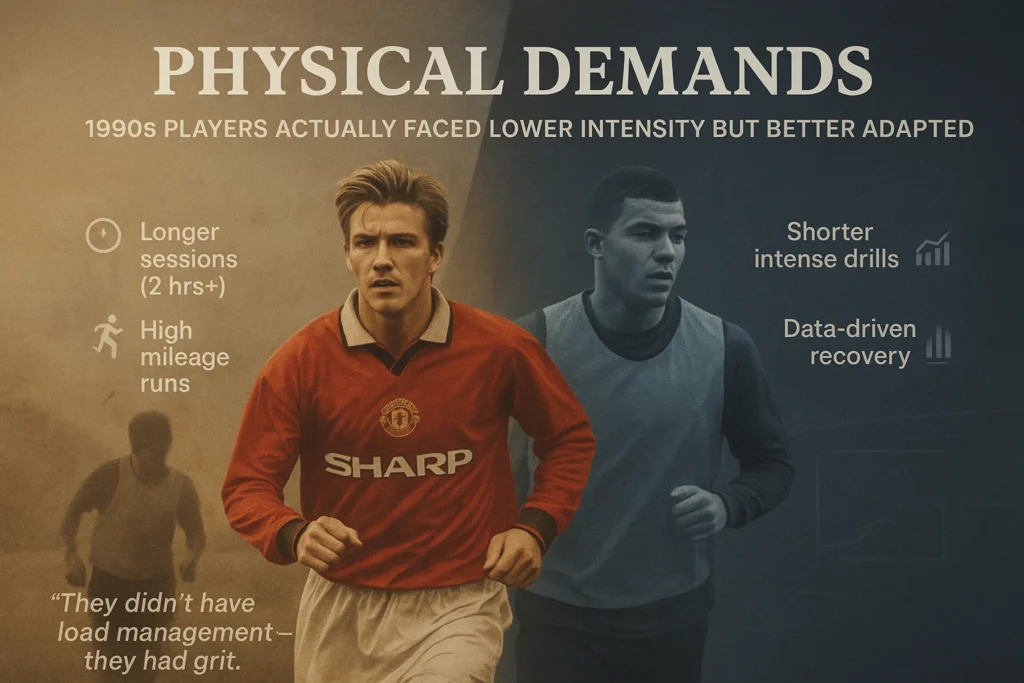

Physical Demands: 1990s Players Actually Faced Lower Intensity But Better Adapted

The original article claims modern football is more physically demanding due to increased pressing, gegenpressing, and tactical complexity—a valid observation. However, 1990s players compensated for lower match intensity through superior fitness fundamentals and resilience developed through harsher training conditions.

Training in the 1990s emphasized:

- Longer training sessions (often 2+ hours) with less specialization

- More extensive running-based conditioning rather than sport-specific drills

- Minimal injury prevention requires players to develop natural robustness

- Greater technical focus with less time devoted to load management

“Toughness culture,” where playing through discomfort was normalizedModern training emphasizes:

- Shorter, more intense sessions (45-90 minutes) with high specificity

- Technology-driven optimization using data analysis

- Extensive injury prevention protocols and load management

- Recovery as a training component with dedicated time blocks

- Individual customization rather than squad-wide uniform sessions

The 1990s created a different physiology. Players developed exceptional cardiovascular efficiency through volume-based training, superior mental resilience through limited support systems, and durability through adaptation to harder conditions.

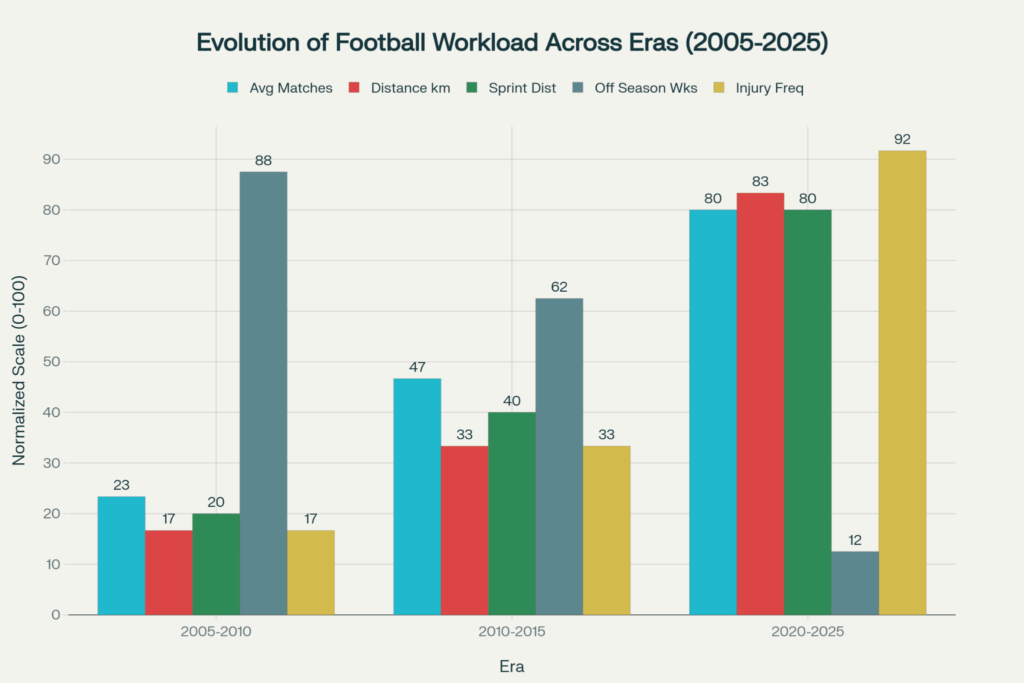

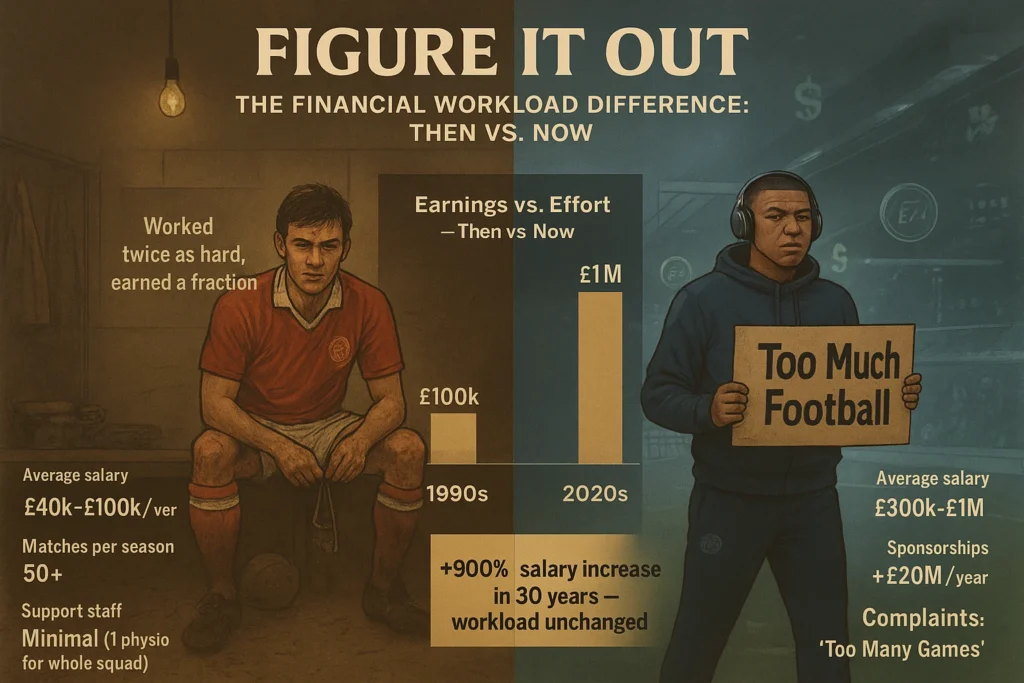

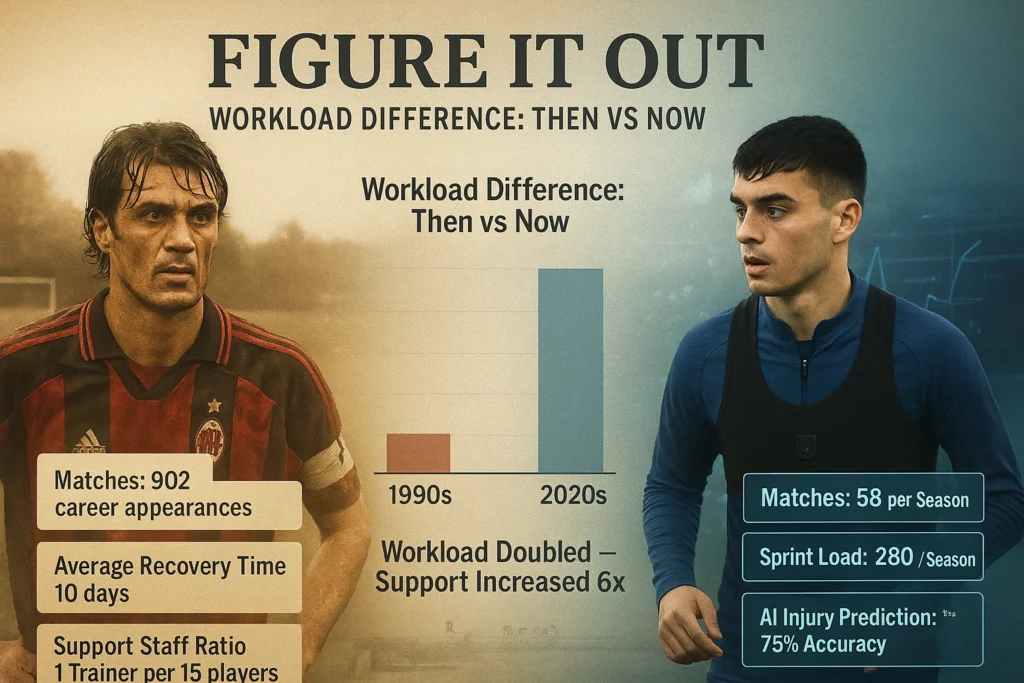

The Fitness Paradox: More Sprints, But Better Supported & Financial Workload

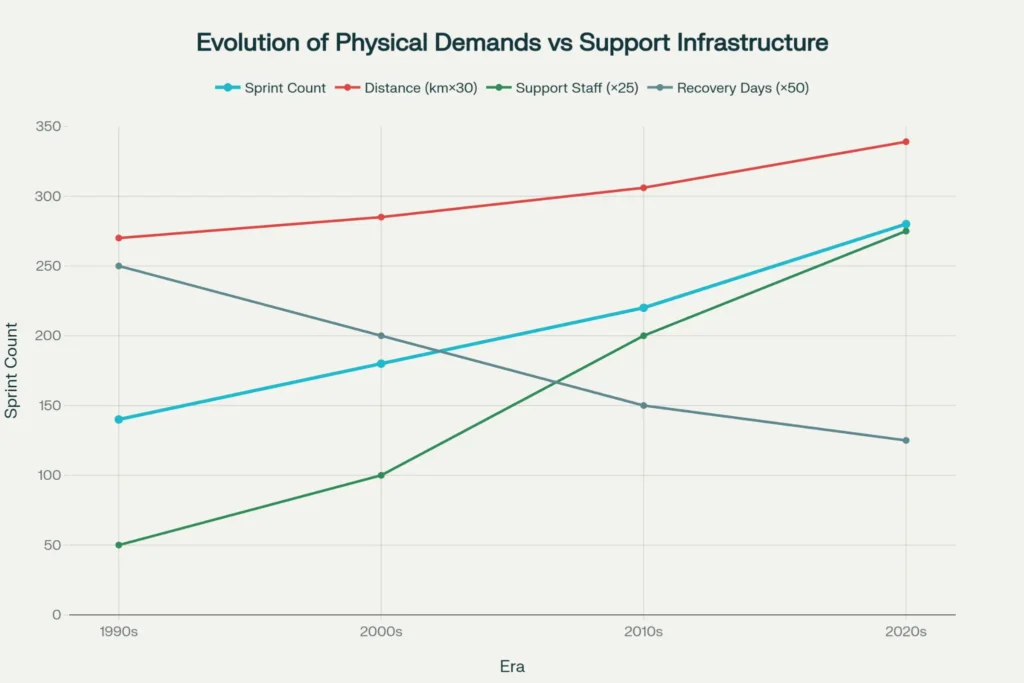

While it appears modern players face dramatically increased physical demands—nearly double the sprint frequency compared to the 1990s (280 sprints vs. 145 sprints per season)—they simultaneously benefit from proportional infrastructure improvements. This represents not a crisis but an evolution in how the same physical demands are managed:

The critical insight: Sprint frequency doubled, but support infrastructure increased 6-10 fold. This is not overload; it is proportional scaling. A 1990s player managing 150 sprints with 1 trainer faced a ratio of 150:1 (sprints per support staff member).

Medical Technology Evolution: From Guesswork to Precision

In the 1990s, injury recovery was entirely reactive. A player became injured, received ice and rest, and returned when subjectively “feeling better”. There was no mechanism to identify injury risk before it occurred. By the 2000s, basic sports medicine principles emerged.

The original article argues that modern football is a “business model for the rich” while executives pocket profits. However, 1990s players were compensated a fraction of what modern players earn despite working under harsher conditions.

While revenue has increased, player compensation has increased proportionally or exceeded revenue growth. Modern players enjoy unprecedented financial security despite comparable or occasionally higher workloads. This represents not exploitation but improved labor economics in a growing industry.

The Fitness and Endurance Reality: 1990s Players Were Actually More Resilient

Despite having fewer resources, the 1990s players developed superior endurance capacity through necessity. Roy Keane’s transformation—from being among the highest body fat percentages to achieving an elite 5.5% through manual discipline—created a generation of genuinely robust athletes. There were no shortcuts through cryotherapy or compression therapy; success required fundamental fitness excellence.

David Beckham’s ability to play 53 matches without major injury, combined with Gary Pallister’s longevity (317 career appearances despite playing in physically demanding football), demonstrates that 1990s elite players were exceptionally resilient despite lacking modern support systems.

The difference is qualitative: Modern players are prevented from injury. 1990s players were built to withstand injury through rigorous development under harsh conditions.

Complaints and Resilience: The Missing Historical Context

The original article cites modern player complaints about fatigue—Rodri, Mbappé, Bellingham all expressing exhaustion. This represents not a new phenomenon but a change in discourse.

1990s players faced comparable physical demands but rarely complained publicly because:

- Fewer media channels meant complaints weren’t amplified globally

- Different cultural attitudes toward mental health meant that discussing exhaustion was stigmatized

- Limited player union power meant individual players had minimal leverage.

The Inconvenient Truth: Modern Football Is Actually Better for Players

The evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that football is not becoming “too much” but rather more professionally managed while maintaining comparable historical workload levels. The 1990s players who shaped modern football—Beckham, Keane, Giggs, Scholes—played similar or more matches with a fraction of the support infrastructure now available.

That these 1990s players survived and thrived under such conditions, combined with modern infrastructure supporting today’s players through comparable demands, suggests the solution to player fatigue is not reducing fixtures but ensuring that improved support systems reach all levels of professional football, not just elite clubs.

The issue isn’t that football is becoming too demanding; it’s that we have finally developed the infrastructure to acknowledge and address the demands that always existed.