Opinions have been hurled across social media for quite some time over the last few months that football is becoming a mere business model for the rich. Organizations and Boards are filling up their pockets without caring for the ones who actually drive this sport.

Can you guess who the driver is? Yes, the players. Modern football has evolved into a year-round spectacle. Between league fixtures, continental tournaments, pre-season tours, and international duties, players are rarely given time to rest.

Is football becoming tiring? Is this the sole reason for more frequent and prolonged injuries of the players?

Is the schedule too tight?

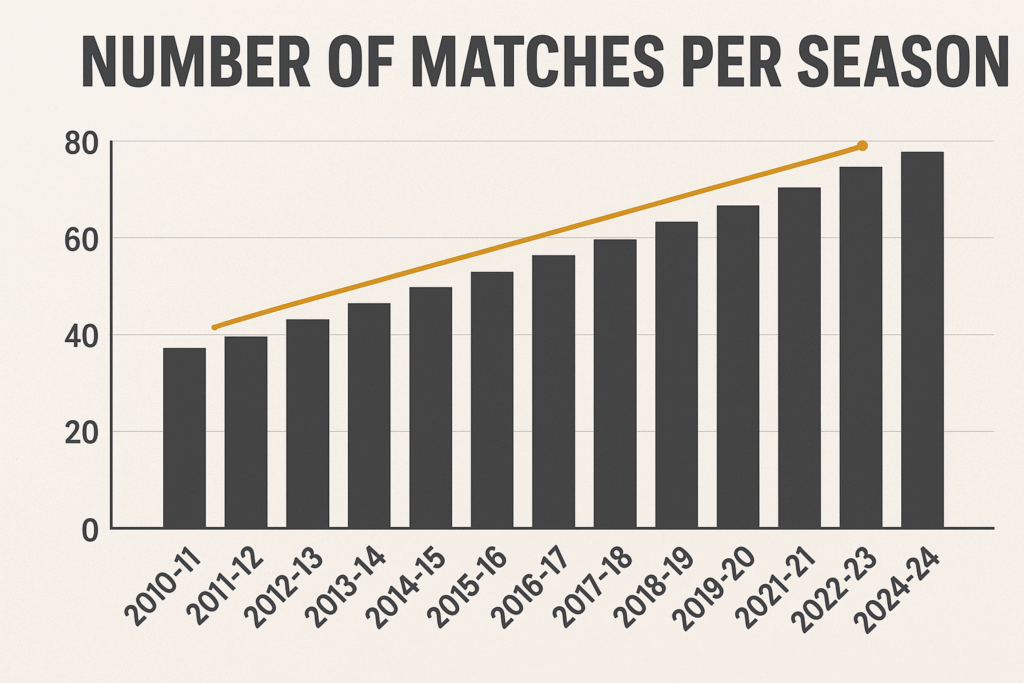

The first question everyone raises in today’s time is whether the number of matches a player, on average, plays is more. Is it really true? Let’s compare data from the last 5 years with the 2010-2015 era.

| Era | Average Matches per Season (Top Players) | Playing Intensity (km covered per match) | Sprint Distance / Explosive Runs | Average Off-Season Break | Injury Frequency (muscle injuries per 1000 hours) |

| 2005–2010 | 52–55 | ~9.5 km | ~150 sprints | 5–6 weeks | ~2.5 |

| 2010–2015 | 55–59 | ~10 km | ~200 sprints | 4–5 weeks | ~3.0 |

| 2020–2025 | 60–64 | ~11–12 km | ~300+ sprints | 2–3 weeks | ~4.5–5.0 |

*(approximate data compiled from FIFA, UEFA, and Sports Science studies)

The number of matches has gradually increased. One might argue it is just 5 matches over the 5 years, but this has resulted in some serious consequences.

Other Factors

Match Intensity, Not Just Quantity – In the 2000s, the tempo was slower, and pressing systems were less demanding. Now, 5 extra matches means 5 times more high pressing, counter-pressing, and positional play. Players have to cover more ground at higher speeds and have less passive recovery during matches. Every 90 minutes today burns significantly more energy than 15 years ago.

Due to this, a break is observed before half-time for drinks and refreshments if the temperature is high.

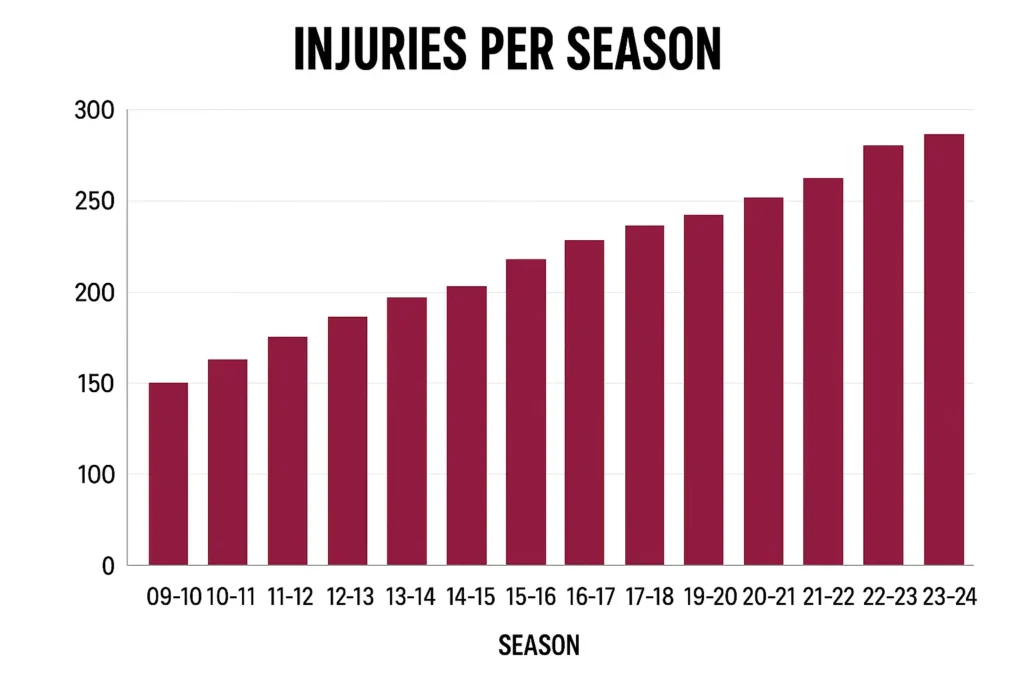

Less Recovery Time- Off-seasons are shorter because of expanded tournaments (UEFA Nations League, new Club World Cup) and post-season tours. COVID-19 has laid down serious long-term but slow health impacts, which are visible in players too. In the 2000s, players often took full rest periods.

Now, the pressure to return early (due to packed schedules and club dependence) means shorter recovery times, which increases re-injury rates. UEFA injury audit (2022–23) shows a 20% rise in muscle re-injuries compared to a decade ago.

Now, the pressure to return early (due to packed schedules and club dependence) means shorter recovery times, which increases re-injury rates. UEFA injury audit (2022–23) shows a 20% rise in muscle re-injuries compared to a decade ago.

Travel Fatigue- To earn more money and to garner more fans from around the world, European Clubs do pre-season tours across Asia, the US, and the Middle East. This thing was not that common and frequent a few years back. This increases time zone fatigue, and players lose energy due to long sitting tours.

Most recently, Kairat Almaty have become only the second Kazakh team in history to reach the Champions League’s league phase. Real Madrid had to travel to Kazakhstan to play their away game.

| Period | Typical pre-season / commercial tour distance (per top club, annual) — estimate | Estimated total annual travel (pre-season + competitive away matches + internationals) — estimate range | Key evidence/examples |

| 2010–2015 | ~15,000 – 30,000 km | ~60,000 – 120,000 km | FC Barcelona reported traveling ~30,000 km in the 2013 pre-season. Real Madrid and other clubs also undertook very long tours in this era. |

| 2015–2020 | ~8,000 – 25,000 km (more variability; some years clubs deliberately cut km) | ~50,000 – 110,000 km | Clubs began sometimes reducing mega-tours after criticism — e.g., Barça cut pre-season from ~22,000 km to <10,000 km in 2016; Real reduced from very large totals to ~18,892 km in 2016 pre-season. But many clubs still did long commercial trips. |

| 2020–2025 | ~10,000 – 35,000 km (COVID dip in 2020, then rebound) | ~60,000 – 140,000 km | Pandemic (2020) briefly reduced tours; from 2021 onwards, big clubs resumed global touring, often adding trans-continental trips (USA, Asia, Middle East). Reporting shows clubs again planning multi-continent tours and “jaw-dropping” air miles. PlayTheGame / media pieces highlight major increases in flight miles from commercial scheduling. |

Youth Overload- Clubs push young stars (Pedri, Gavi, Bellingham) into 50+ match seasons by age 18–19. Earlier, young players were eased into the squad. Overexposure at young ages can cause chronic fatigue and long-term muscle damage. Pedri played 73 matches at age 18; Xavi or Iniesta played fewer than 50 at the same age.

Old vs Modern Football. Does it really matter?

The tight schedule is definitely one of the culprits. Players nowadays often argue about it. But here is an interesting comparison.

| Metric | Lionel Messi — calendar year 2012 | Erling Haaland — 2022–23 season |

| Matches (club + country, calendar/season) | 69 matches (calendar year 2012) out of 74 games. | 53 appearances (all competitions, 2022–23) out of 65 games. |

| Goals (club + country/club season) | 91 goals in 2012 (calendar year — Barcelona + Argentina). | 52 goals in 2022–23 (all competitions for Manchester City). |

| Goals per match (raw) | ~1.32 (91 ÷ 69) | ~0.98 (52 ÷ 53) |

| Role/playing style | Attacking forward/playmaker — heavy involvement in buildup, assists, and finishing; often drops deep, creates, and scores. | Center-forward / pure striker — more penalty-box finishing, high conversion of chances created by teammates. |

Messi scored a world record 91 goals in the 2012 season. Haaland, on the other hand, missed 12 games and scored 52 goals. Haaland wasn’t even injured. So why didn’t he play all the games?

Then: Training sessions were shorter, less scientific, and often involved more ball work and less gym work. Recovery days were common. Now: Players undergo double sessions, strength training, and constant physical monitoring. There’s little downtime.

“Players aren’t just playing more. They’re training harder, faster, and with less rest.”

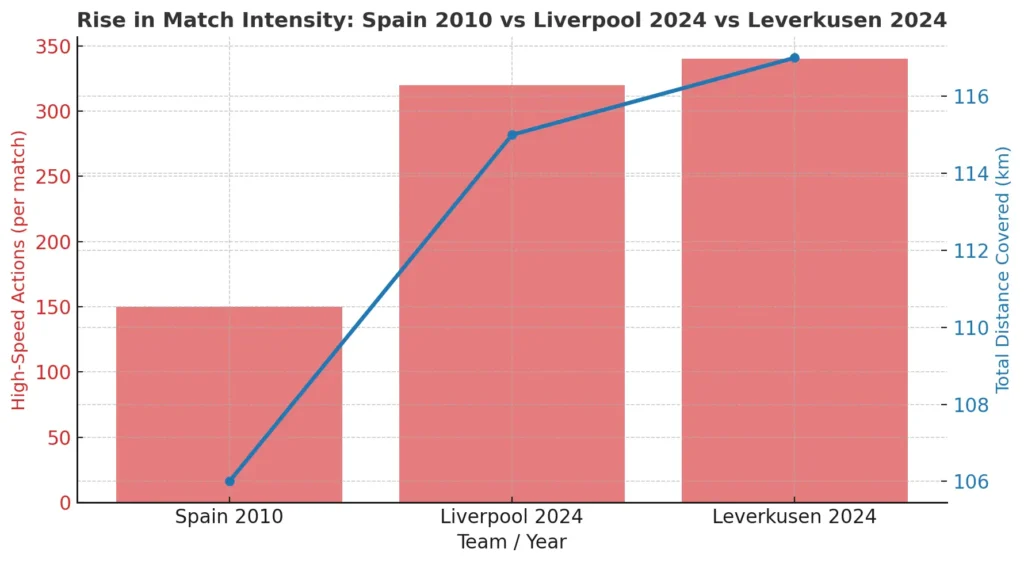

The rise of Gegenpressing (Klopp), positional play (Pep Guardiola), and high defensive lines means every player, even strikers, must constantly press and reposition. In contrast, teams in the 2000s often played with more structure, less pressing, and slower transitions. To understand this, let us compare Spain 2010 (the tiki-taka World Cup champions) vs Liverpool 2024 or Leverkusen 2023–24, both high-intensity, press-heavy sides.

The rise of Gegenpressing (Klopp), positional play (Pep Guardiola), and high defensive lines means every player, even strikers, must constantly press and reposition. In contrast, teams in the 2000s often played with more structure, less pressing, and slower transitions. To understand this, let us compare Spain 2010 (the tiki-taka World Cup champions) vs Liverpool 2024 or Leverkusen 2023–24, both high-intensity, press-heavy sides.

| Aspect | Spain 2010 (World Cup era) | Liverpool 2024 / Leverkusen 2023–24 | What It Means |

| Tactical identity | Controlled possession (Tiki-Taka): deliberate tempo, short passing, positional play. | High-intensity transition football: vertical attacks, high pressing, quick turnovers. | Matches today have more high-speed phases even with equal ball-in-play time. |

| Avg. team possession | 65–70% per match (Spain often exceeded 70%). | 55–60% (Liverpool/Leverkusen), but at a higher tempo and speed. | Modern teams don’t dominate possession as long; they maximize intensity per second. |

| Avg. passes per 90 mins | 700–800 (Spain at 2010 WC averaged 637; some matches >800). | 500–600, but with quicker ball progression and more sprints. | Fewer passes, but faster rhythm and higher physical toll. |

| High-speed runs (>25 km/h) | ~100–150 per team per match (est., 2010 standards). | 250–350+ per team per match (Liverpool & Leverkusen 2023–24). | Nearly 2–3× more explosive efforts per 90 minutes today. |

| Distance covered at high intensity (>19.8 km/h) | ~8–10 km per player per match. | ~12–14 km per player per match (especially full-backs & forwards). | Players today cover more distance at higher intensity, which means more fatigue even with the same match count. |

| Recovery & match rhythm | Longer spells of slow build-up allowed micro-rests in play. | Press–sprint–recover cycles, fewer low-tempo moments. | Less recovery “within” the game itself; sustained physical strain. |

| Tactical rest periods | Yes, Spain recycled possession across midfield to slow the tempo. | Minimal, gegenpressing systems push constant defensive-offensive transitions. | Modern players burn energy continuously. |

| Injury & fatigue trends | Fewer muscular injuries linked to overuse; slower pace. | Spike in hamstring/soft-tissue injuries since the 2020s. | Modern load + speed is physically harsher. |

Football Stars (Then vs Now)

Football Stars (Then vs Now)

For a final gist, let us try to make a rough idea between stars of modern and past football by comparing match statistics and their physical condition.

Box-to-Box Midfielder

| Player | Age | Matches in First Full Season | Minutes Played | Major Injuries |

| Steven Gerrard (1999–2000) | 19 | 41 | ~3,200 | Minor groin issues only |

| Jude Bellingham (2023–24) | 20 | 42 | ~3,700 | Shoulder injury mid-season; managed load carefully |

Holding Midfielder

| Player | Age | Matches in Breakthrough/Peak Season | Minutes Played | Major Injuries |

| Sergio Busquets (2008–09) | 20 | 41 | ~3,000 | 0 major injuries |

| Declan Rice (2023–24) | 24 | 52 | ~4,400 | None reported; high physical load sustained |

Midfielder

| Player | Age | Matches in First Full Season | Minutes Played | Major Injuries |

| Xavi (2000–01) | 20 | 47 | ~3,600 | 0 major |

| Pedri (2020–21) | 18 | 73 | ~5,300 | 4 muscle injuries in the next season |

Full-Back

| Player | Age | Matches in Peak/Breakthrough Season | Minutes Played | Major Injuries |

| Philipp Lahm (2005–06) | 22 | 38 | ~3,100 | Knee injury recovery early; fit afterward |

| Trent Alexander-Arnold (2019–20) | 21 | 49 | ~4,200 | 1 muscle strain next season (fatigue-related) |

Centre-Back

| Player | Age | Matches in Prime Season | Minutes Played | Major Injuries |

| Carles Puyol (2005–06) | 27 | 52 | ~4,500 | 0 major injuries |

| Virgil van Dijk (2023–24) | 32 | 51 | ~4,400 | Past ACL injury (2020–21); managed fitness load |

Winger / Forward

| Player | Age | Matches in Peak Season | Minutes Played | Major Injuries |

| Cristiano Ronaldo (2011–12) | 27 | 55 | ~4,800 | None significant |

| Kylian Mbappé (2023–24) | 25 | 52 | ~4,300 | Recurrent ankle/muscle strains managed with rest |

Professional Institutes Researches

A study from the University of Kent found that mental fatigue reduces running, passing, and shooting ability in footballers. ScienceDaily

According to a survey published by FIFPRO, many elite players say “the schedule is getting busier and busier” and that they feel “mentally and physically exhausted”. FIFPRO

A report ahead of the 2022 World Cup noted players were playing “non-stop … like a washing machine” due to compressed schedules and little rest. Deutsche Welle

The Call for Change

Here are notable footballers and coaches who have expressed their concern with the schedule and fatigue.

| Person | Quote / Summary |

| Rodri (Manchester City) | “I think we are close to that (strike) … If it keeps going this way, there will be a moment where we have no other option.” |

| Kylian Mbappé (Real Madrid / France) | “It’s too much. Today was too much. We played 120 minutes less than three days ago.” |

| Jude Bellingham (Real Madrid) | “Mentally and physically, you are exhausted.” |

| Jules Koundé (Barcelona / France) | Warned that the packed calendar is harming the entire football ecosystem, including the families of players. |

| Mikel Arteta (Arsenal) | Called the excessive number of games “an accident waiting to happen.” |

| Simone Inzaghi (Inter Milan) | “There’s both physical and mental fatigue — we need to be stronger than all of that.” |

| Pep Guardiola (Manchester City) | “If you want to say I’m complaining about the schedule. OK, I am complaining.” |

| Kevin De Bruyne (Napoli) | “I feel mental fatigue more than physical. There’s barely time to rest between tournaments and seasons. It’s exhausting.” |

| Raphaël Varane (Manchester United / France) | “We are playing too much football. We’re not robots. It’s affecting our mental health and increasing injuries.” |

| Karl-Heinz Rummenigge (Bayern Munich) | “Our players should stop complaining!” A contrasting view defending the busy schedule. |

The Money Factor

It’s no coincidence that at the same time players are complaining of fatigue, the sport is minting money like never before. With the UEFA men’s club competitions alone projected to generate €4.4 billion in 2024-25, and Europe’s top 20 clubs pulling in €11.2 billion in 2023-24, the commercial machine is running at full speed. Reducing fixtures, extending rest periods, or dialing back tournaments would risk disrupting revenue flows. In short, the business model of modern football often runs at odds with player welfare.

The fact that UEFA is projecting €4.4 billion for club competitions and knowing only a small portion is retained as operational margin indicates that the business model relies on maximizing fixtures, global reach, and high-intensity competitions.

The Future of Football: More Matches or More Magic?

If overloading continues, the sport risks lower quality and shorter careers. There are fewer players nowadays who have the profile like that of Messi, Ronaldo, Eden Hazard, Maradona, Roberto Carlos, etc, who used to go out of the box, forget the tactics, and produce individual moments like dribbling past an entire team, scoring free kicks from yards out, and taking long shots.

We, as football fans, not only remember each frame of those moments but also the commentary pieces too.

“Too far for Ronaldo to think about it”, “Away from 2,3,4 wonderful, wonderful, wonderful”, “Ankara Messi”, “Ohhh you beauty! What a hit, son! What a hit!”

The beautiful game is running faster than ever. But it might be running itself into exhaustion.