Picture this: it’s the year 2000. Nike drops an ad where Edgar Davids, Figo, and Totti fight robot samurai inside a fortress just to steal a football.

That ball—the Nike Geo Merlin—would go on to become the official Premier League match ball, kicking off a partnership that lasted two decades.

For fans growing up in the 2000s, Nike wasn’t just another sponsor. Nike was football.

Thierry Henry’s finesse, Ronaldo’s stepovers, Rooney’s volleys, Agüero’s title-clincher—the swoosh was always in the frame.

But fast-forward to 2025, and things look very different. Nike has lost the Premier League ball deal.

Liverpool is walking back to Adidas. Portugal ended a 27-year partnership. Even superstar players like Harry Kane have ditched them—for Skechers of all brands.

So, how did Nike—the brand that once defined football culture—lose its grip on the game? And more importantly, is this the end of Nike in football, or just the start of something new?

The Fall of the Swoosh?

From Oregon to the World: How Nike Crashed Football’s Party

Nike wasn’t born in football. The company started in Oregon in 1964 as Blue Ribbon Sports, selling Japanese running shoes.

By the 1980s, Nike dominated American sports thanks to a certain Michael Jordan.

But outside the U.S.? They were nobodies. Adidas and Puma owned football. They had the boots, the kits, the World Cup contracts. If Nike wanted to go global, they needed football.

And Phil Knight, Nike’s CEO, saw the opening. His logic was simple: the road to world domination runs through Brazil.

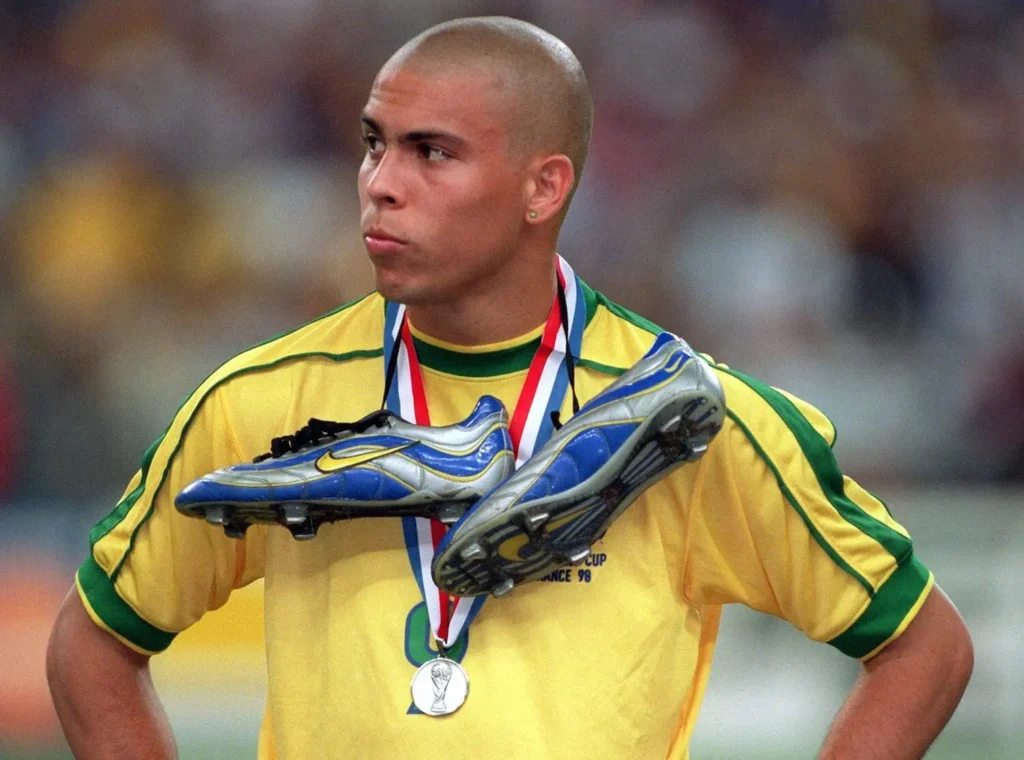

In 1996, Nike signed Brazil for a then-record $200 million. Six years later, Ronaldo, Rivaldo, and Ronaldinho—head-to-toe in swoosh gear—won the 2002 World Cup. Boom. Nike had arrived.

From there, Nike went all in. They signed up Arsenal, Barcelona, Inter, PSG, and Manchester United. They grabbed national teams like France, Portugal, and the Netherlands.

And they turned advertising into art: the airport ad, the cage tournament on a ship, the Joga Bonito campaign.

By the 2010 World Cup, Nike wasn’t just part of football. They were football.

Nike’s Peak: The Age of Superstars

Nike’s empire was built on faces. Ronaldo Nazário, Ronaldinho, Rooney, Iniesta, Zlatan, Cristiano Ronaldo.

Their boots weren’t just products—they were icons. The Total 90s, the Mercurials, the CTRs. Every kid had a Nike poster on their wall.

And the business matched the hype. In the 2014 World Cup, Nike outfitted 10 national teams (more than Adidas or Puma).

In the three months after that tournament, Nike’s revenue jumped 15% to $8 billion.

Nike didn’t just sponsor football. They shaped football culture—from what fans wore, to how they consumed the game, to the music they heard in FIFA.

But here’s the problem: when you build your empire on superstars, what happens when football itself changes?

Cracks in the Swoosh

The first warning signs came quietly. Roma and Inter Milan’s deals ended.

Neymar walked away in 2020 after 15 years. The Premier League ball contract—gone after 23 years. Portugal, the CR7 nation, left Nike after nearly three decades.

At the same time, Nike’s designs started slipping. The company that gave us the bold Brazil kits of 2002 and the timeless Total 90s began churning out jerseys that looked like copy-paste Canva templates.

The 2022 World Cup? Nike had 13 national teams, the most of any brand, yet none of their kits felt memorable. Fans noticed. And they didn’t hold back online.

Meanwhile, Adidas and Puma smelled blood. Puma signed Neymar. Adidas doubled down on iconic designs and snatched Liverpool back from Nike.

Even smaller brands like Castore and New Balance started landing clubs.

And in the most symbolic blow of all, Harry Kane—England captain, Tottenham legend—signed with Skechers. Yes, Skechers.

Why Did Nike Step Back?

So what went wrong? Did Nike just stop caring about football? Not exactly.

Insiders say Nike’s football division became “uninspired and detached.” Risk-taking slowed. Innovation dried up.

Meanwhile, competitors got sharper. Adidas went back to its roots. Puma went all-in on flair.

But more importantly, football itself changed. Today’s game is less about vibes and individual brilliance and more about systems, tactics, and data.

In the Instagram era, footballers might have bigger followings, but fewer of them carry the global superstar aura of a Ronaldo or Ronaldinho.

And that’s a problem for Nike, because Nike’s empire was built on stars, not systems.

Nike’s New Play: From Matchday to Streetwear

Nike isn’t quitting football. They’re just changing the rules.

Instead of pouring billions into club-wide contracts and national teams, Nike is pivoting to football culture over football performance. Translation: less about kits and boots, more about lifestyle and identity.

Think capsule drops. Retro reissues. Streetwear collabs. TikTok campaigns. Instead of making the kits players wear, Nike wants to own the outfits they walk in with.

They’re sticking with Mbappé and Haaland as poster boys. They’ve renewed Barcelona until 2038, France until 2034, and PSG until at least 2027.

And they’re banking on retro hype—the final Premier League Nike ball is a throwback to the classic T90. They even launched “The Cage” again, this time with Travis Scott.

In short, Nike doesn’t want to dominate the 90 minutes anymore. They want to own everything around it.

What This Means for Football

Nike’s leaving the pitch creates a vacuum. Adidas and Puma dominate technically, but neither has Nike’s flair for storytelling.

Clubs could lose bargaining power if brands focus more on individuals.

Fans could see less unity, more fragmentation—your favorite player’s brand might matter more than your club’s kit deal.

For Nike, it’s a gamble. If their lifestyle-first strategy clicks, they’ll reshape football culture again. If it fails, they risk becoming outsiders in a sport they once ruled.

Either way, one thing is clear: the swoosh doesn’t shine as brightly in football as it once did.

FAQs

Q: Why is Nike leaving football?

Nike isn’t leaving completely—they’re shifting from big club and league deals to focusing on superstars, streetwear, and lifestyle culture.

Q: Which clubs and countries has Nike recently lost?

Nike lost Liverpool, Inter, Roma, Portugal, and the Premier League ball deal. Neymar and Harry Kane also left their personal contracts.

Q: Who are Nike’s main football stars now?

Kylian Mbappé and Erling Haaland are Nike’s two biggest football faces heading into the 2026 World Cup.

Conclusion: Is the Swoosh Fading or Evolving?

So, is Nike losing at football? On the pitch—yeah, it sure looks like it. Losing Liverpool, Portugal, and the Premier League ball hurts.

Fans think their kits have gone downhill. And Adidas and Puma are circling.

But Nike has always thrived on reinvention. Just like they turned basketball into a cultural empire with Air Jordans, they’re now trying to turn football into a lifestyle brand.

Will it work? Only time will tell. But one thing’s for sure: when Nike plays, they don’t just play to compete—they play to change the game.